A funny old book

There’s a town on Vancouver Island called Qualicum Beach. It’s a nice little town which I’ve visited a few times. With one exception the reason I’ve gone there is to see a play. The first time I went to see a play there I discovered my favourite thing about the town: A few doors up the road from the theatre there’s a lovely independent bookshop, the Mulberry Bush.

The first time I went into this shop several years ago, every one of Ian Hamilton’s Ava Lee novels were in the mystery section. Now this is unusual in a small bookshop with limited shelf space. At that time I’d never heard of the series, so I read the back cover of the first and thought it sounded interesting. When I asked the woman who worked there why they had the whole series she told me it was because everyone who read the first one wanted immediately to read the rest. Sold.

I did enjoy the book and I did indeed carry on with the series for many years, although my interest faded quite a bit when she stopped working with Uncle.

When I find myself in Qualicum Beach for any reason I always go into the Mulberry Bush and buy at least one book for all the reasons they list on their bookmarks. (Oh, to have a shop like this here on the island!) And I usually discover an author who is new to me.

A play took me to Qualicum Beach last month and of course I had a good old browse around the Mulberry Bush.

They had Rachel Maddow’s new book, Prequel, about the fascist movement in the US in the 1930s, which I am interested in reading. They also had Liz Cheney’s book, which I’m kinda interested in reading, but can’t quite get past giving her money, even if she has turned out to be one of the few heroes of the once Grand Old Party. And some other non-fiction that looked interesting.

Okay, but what about the mystery section?

Names I knew, names I’ve never heard of and one name with which I was familiar, but not as a writer of mysteries.

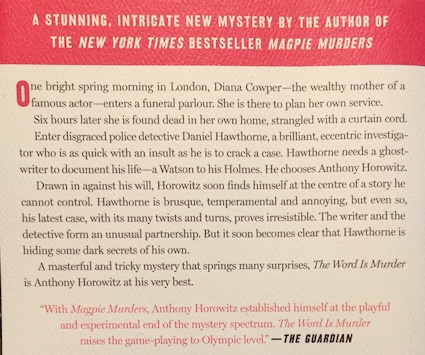

I recognised the name Anthony Horowitz. I knew of him as the creator of Foyle’s War and Midsomer Murders. I also knew he’d written the screenplay for The Magpie Murders, which I watched not all that long ago. I didn’t know it had originally been one of his novels. I’d always thought of him as a television writer and had no idea he was also a novelist. I can’t remember ever seeing a novel by Horowitz in the mystery section of any bookshop, which is odd, as it turns out he’s written dozens.

I read the back cover.

Hmm. Sounds… I don’t know. Interesting? Has possibilities?

It was down to this, The Word Is Murder, or another mystery by another author of whom I’d never heard. I had a nice pile of Christmas books beside the bed and didn’t really need to add to it, but I couldn’t come to Qualicum Beach without buying one book from this shop. I took both to the counter and held them up for the woman working there that day. “Which one?” I asked. She told me she didn’t know anything about the second book (I’ve already forgotten what it was), but the owner had loved the Horowitz. “It does,” I conceded, “sound interesting, particularly him inserting himself into the novel as a character.” She looked surprised when I mentioned this. Well, it is surprising. So I bought it.

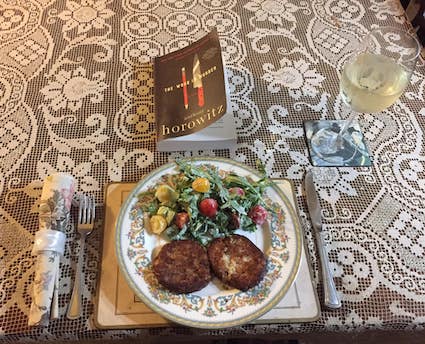

This is a funny old book.

You read the first chapter and it starts off sounding like many mystery novels before it. Then you get to the second chapter, written in first person by Horowitz and detailing the approach made to him by Daniel Hawthorn, former member of the Murder Investigation Team at the Met, now a consulting detective for them (first bit of shades of Sherlock Holmes), who’d recently worked with Horowitz as a consultant on Injustice, a television series. (This is an actual series that Horowitz wrote.) Hawthorne wants Horowitz to write a true crime book about his investigation of the murder detailed in chapter one.

I’m reading this and thinking, ‘Wait a minute. Is this a novel or is it actually a true crime book? Did this happen?’ Stop reading to go online and do a search. No, it is a novel with Horowitz as a character. There is a lot of fact blended into this fiction. For example, Horowitz writes about a meeting he did in reality have with Steven Spielberg and Peter Jackson about a possible script for a Tintin sequel. In the novel this meeting is interrupted by the untimely arrival of Hawthorne.

It’s a strange conceit, but once you get past that it works. And no one who likes a good red herring could complain about a lack thereof.

When I finished reading it in bed last night, I discovered that it is the first in a series with the first chapter of the next one, The Sentence Is Death, available to read in the back pages. I read it and, yeah, I’ll probably buy the book – but not until the Christmas pile is gone.